In the previous post I walked the first part of the Roman Way from London to Lewes, from the New Cross/Peckham area to Blythe Hill – or rather, I tracked it at a distance, because what’s special about this Roman road is its stubborn refusal to conform to modern roads or paths. But that will change, as we shall see.

The engineers who built the Lewes Way shifted its alignment fractionally to the south at Blythe Hill, aiming across Stanstead Road and Catford Hill for a crossing point on the River Pool. Rather wonderfully, that crossing point is still in use 2,000 years later. The modern bridge is at exactly the same place, in the River Pool Linear Park.

In the 1930s our intrepid archaeologists, Davis and Margary, revealed the line of the Way here on the eastern bank of the river

where it cuts diagonally from right to left to cross the railway line and head into Bellingham.

Here its course runs through houses and gardens as it heads south-south-east towards Beckenham, but we can still identify certain marker points. For instance, this is where it crosses Stumps Hill Lane

before continuing over Southend Road, and hitting the old London Chatham and Dover railway line a couple of hundred yards’ east of Beckenham Junction Station.

From here the Way tracks the course of the River Beck, before cutting across the south-east corner of Kelsey Park, conveniently close to the café where I reckon I had earned the right to a refreshing cuppa.

I was now deep in leafy suburbia, and the next marker point was St. Dunstan’s Lane which wanders quietly through a landscape of sports grounds and playing fields and golf. Just where the Lane turns from a south-westerly to a near-southerly direction, the Lewes Way comes through, still on its south-south-east trajectory.

It ploughs straight through the golf course – no bad thing in my opinion – to cross the Charing Cross to Hayes railway line almost exactly at West Wickham Station.

The next marker point was Sparrow’s Den, at the bottom of Corkscrew Hill, south of West Wickham, where the road cuts across the playing field. Here we are close to a Roman settlement just across the road, near St. John the Baptist church.

This is one of many sites in South London to be nominated as the ‘lost city’ of Noviomagus, which lay somewhere on an imperially-endorsed route from London to Rochester. Clearly there was a Roman settlement here – excavations prove that. But as I’ve argued at length in a previous post, the notion that West Wickham is Noviomagus makes no sense. Who would travel from London to Rochester via West Wickham?

The course of the Way meanwhile carries on, south-south-east, across the fields, gradually approaching the New Addington estate. And here at last, after all those miles of hiding in suburban gardens and scuttling across railway lines, the Lewes Way deigns to correspond to a modern way in the modern landscape.

From Addington Road I took a foot-path which climbs south-east through Birch Wood towards Castlehill Ruffs. It was not marked on the OS map as a public right of way, but neither was it marked on the ground as private or with warnings against trespass. It is clearly regularly used as an informal way up to the New Addington estate. After a bit less than a mile the path crossed a rough vehicle track, and I turned left for a couple of hundred yards along this track towards an electricity sub-station. Just before the sub-station I turned right again onto a new foot-path heading south-south-east through Rowdown Wood.

I was now, finally, walking the line of the Lewes Way, the first time I had been able to do so since leaving Watling Street.

The path continued through the woods, not arrow-straight by any means but not deviating wildly either, edging closer to New Addington’s eastern border. It hit this border right at its most unattractive point, next to the industrial zone. Suddenly, what had been a pleasant enough woodland walk became a grim urban edgeland slog, pinned between an ageing concrete fence to the right, and shabby undergrowth to the left, littered and scattered with rubbish and debris of all kinds.

This grubby scramble didn’t last for ever. Once it got beyond the industrial area and backed onto housing, the path became more pleasant. And even when it was at its worst I tried to remind myself that I was walking the line not of a pristine Roman military highway, but of a working industrial road whose job was to link the manufacturing zone of the Weald with markets and barracks in Londinium. So maybe the waste scattered along the path was fitting, a grim nod of recognition from one industrial era to another, expressed in refuse.

This grubby scramble is also, by the way, the line of the modern borough boundary between Croydon and Bromley, which follows the much older county boundary between Surrey and Kent. And this in turn suggests that the course of the Lewes Way across this particular landscape was very clear in early medieval times, offering itself as a ready-made marker just when these two English counties were defining themselves and acquiring firm borders.

The path finally emerges on the southern edge of New Addington, a few yards from Fairchild School, and opposite a Bromley Borough post to confirm that we are indeed right on the old county boundary.

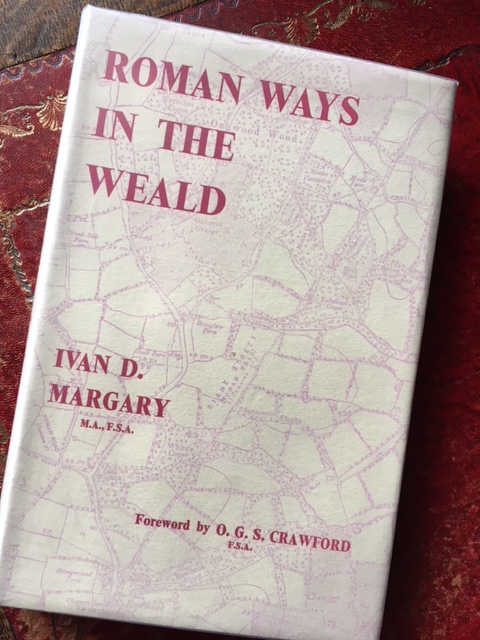

That’s as far as I intend to follow the Lewes Way. If you fancy carrying on, I suggest you try to get hold of a copy of Margary’s 1948 classic Roman Ways in the Weald.

It is of course out of print, but there were copies available through abebooks.co.uk last time I looked, and if that doesn’t work, we still – just about – have libraries. Of course Margary was at work many decades ago, and his arguments have sometimes been superseded by more recent scholarship. But for me, none of this alters the fact that the book itself is a sheer delight, and with a bit of interpretation to make allowance for seventy years of suburban growth, its brilliant maps are still surprisingly useable.